Pangolins are a group of mammals that rarely register in the public consciousness but they are by far the most heavily trafficked animals in the world. A pangolin most resembles an anteater with scales – in fact, it is the only group of mammals that has scales. These prehistoric looking creatures have long tongues that can stretch almost their entire body length – useful for catching ants – they have no teeth and they roll into a tight armoured ball when confronted. Wildlife photographer Suzi Eszterhas, who spent time with the animals in a reserve in Vietnam, said of the pangolin, ‘Some animals you can’t help thinking just seem too innocent for this world. The pangolin is one of those creatures.’

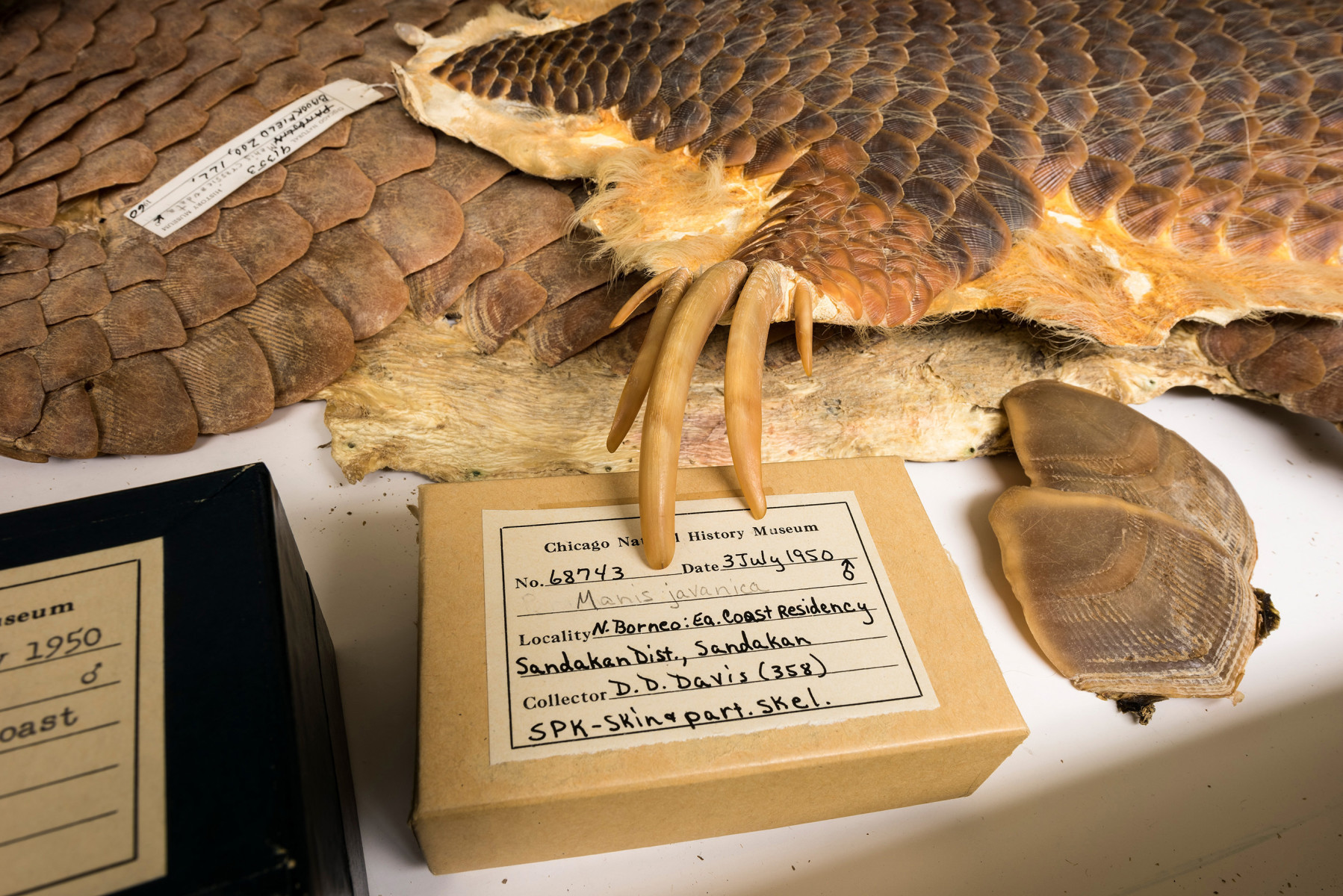

There are currently only eight living species of pangolin, four in Asia and four in sub-Saharan Africa. The Chinese pangolin is distributed across southern China, Southeast Asia and into Nepal and Bangladesh, while the Sunda pangolin’s range extends further south into Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore. The Sunda pangolin is slightly larger than the Chinese pangolin but they share many other similarities, including a preference for forested habitat and sleeping in burrows or tree hollows during the day before emerging at night to hunt for ants or termites.

These two species of pangolin have suffered more than any others due to their location in the world. Their meat and blood is prized as a delicacy and their scales are used in traditional medicines, said to have aphrodisiac properties and to cure skin problems (although they are made of keratin, the same structural protein in human hair and nails). A live pangolin can be sold on the black market for several hundred dollars, a price that continues to rise because of the bans on trade and the lack of enforcement. It is estimated that one million pangolins have been trafficked in the past decade, resulting in an 80 percent decline in their numbers and leaving them disturbingly close to extinction.

As the plight of the pangolin gathers more and more attention, organisations big and small are taking action. Pangolins rescued from poachers are released back into the wild or placed in reserves for captive breeding. Public education is another major hurdle – many people do not know that it is illegal to eat pangolins or fear them because of their appearance – and raising awareness is a focus of organisations like Save Pangolins and Pangolin Conservation. Changing the mentality of an entire continent – enough to put an end to illegal poaching – is, however, a colossal task and unless more practical steps are taken immediately it may prove too late for the innocent pangolin.